Understanding the Bee

To truly support honey bees through treatment-free methods, we must begin by understanding who they are—not just biologically, but behaviorally and ecologically. Bees are not simply livestock; they are wild creatures living in complex societies, attuned to seasonal changes, the cycles of flowering plants, and the subtle energies of the landscape. As beekeepers, we must meet them on their terms, not force them to conform to ours.

The Biology and Behavior of the Honey Bee

Honey bees are remarkably sensitive beings with complex sensory systems. Studies suggest that bees may even experience emotional-like states—such as optimism or stress—based on environmental conditions and interactions. This emotional dimension is still emerging in scientific literature but supports what many beekeepers intuitively observe: that bees respond to the emotional and energetic presence of their keeper. This subtle relational field underscores the importance of approaching hives with calm, presence, and respect.

Bees perceive the world not only through sight and smell but through vibration and electromagnetic fields. Their antennae and body hairs detect shifts in energy, allowing them to navigate and interact with astonishing precision. This heightened sensory awareness influences not only foraging and orientation but also social cohesion and hive decision-making. Understanding this multi-sensory experience helps us appreciate the richness of bee consciousness and supports gentler, more intuitive hive practices.

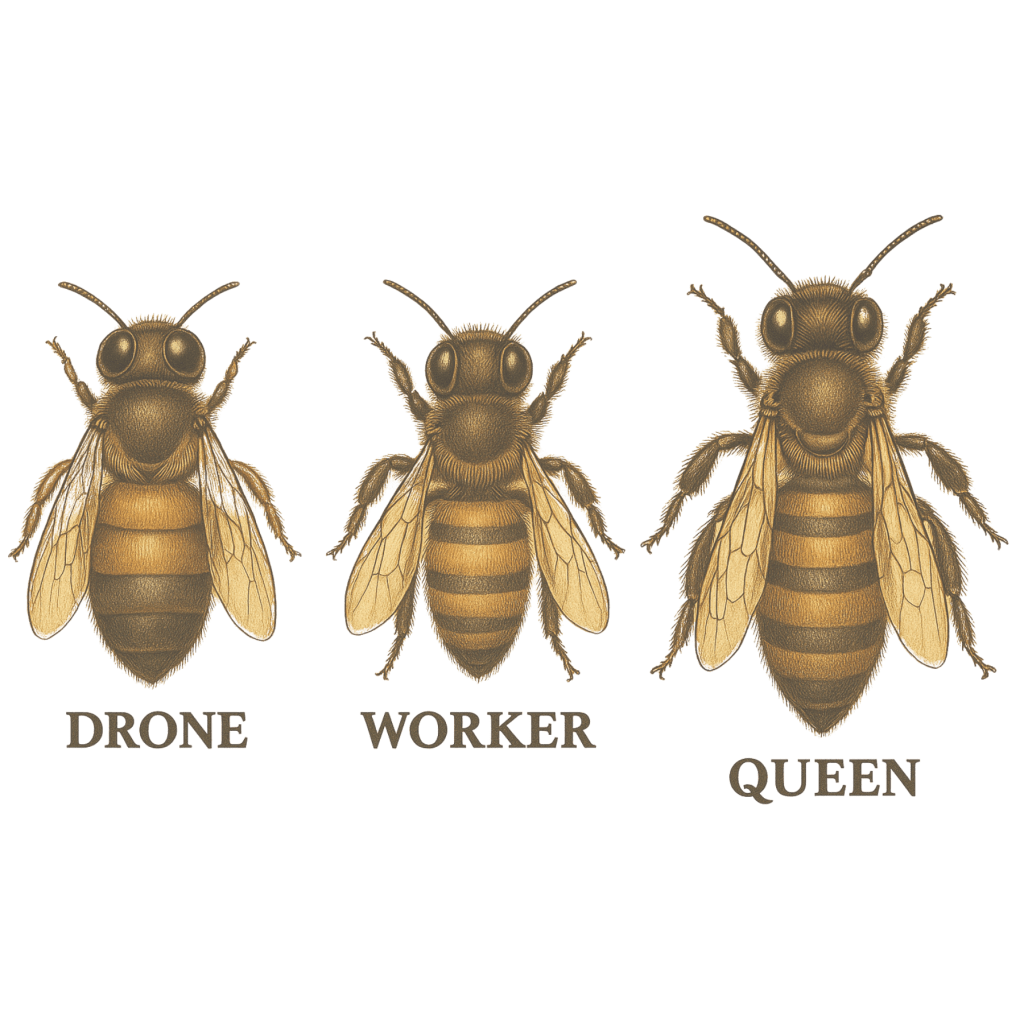

At the heart of the hive lies a dynamic balance between specialization and collaboration. Honey bees are organized into three distinct castes: the queen, workers, and drones. The queen is the reproductive female, while workers are sterile females who perform various tasks, and drones are the male bees. Bees change roles based on pheromonal cues, hive needs, and age, resulting in a self-organizing society that continuously adapts.

We’ll explore the different bee castes in greater depth later in this section.

Communication is fundamental to this coordination. Bees employ a sophisticated language of pheromones—chemical signals that regulate nearly every aspect of hive behavior. These pheromones are secreted by various glands in the bees’ bodies and can be detected by others through olfactory receptors located primarily on the antennae.

One of the most crucial is the queen’s mandibular pheromone (QMP), which maintains social structure by signaling her presence and suppressing worker reproduction. Workers exposed to this pheromone are less likely to initiate queen-rearing behavior. Alarm pheromones, released from glands near the sting, alert other bees to threats and can trigger defensive behavior. These pheromones are particularly volatile and can spread rapidly in the air, mobilizing guards to defend the entrance.

Brood pheromones, secreted by larvae, influence foraging behavior and nurse bee activity, ensuring appropriate care and provisioning. These include E-β-ocimene and other compounds that signal the developmental stage and nutritional needs of the brood. Foragers and house bees also use Nasonov pheromones—a blend of volatile compounds released from a gland near the tip of the abdomen—to help guide other bees during swarming, orientation flights, or when locating food and water sources. When bees raise their abdomens and fan their wings while exposing this gland, they effectively broadcast a homing signal that can unite separated colony members.

Additionally, some pheromones influence reproductive dynamics, such as the drone pheromone, which plays a role in mate attraction and congregation behavior. These chemical messages create a unified awareness across the colony, enabling precise coordination, task allocation, and social harmony. This chemical communication creates a unified awareness across the colony.

In addition to pheromones, bees use movement-based signaling, most famously the waggle dance. When a forager discovers a rich food source, she returns to the hive and performs a figure-eight pattern on the comb. The direction and duration of her waggle convey the location and distance of the resource relative to the sun.

This dance language allows for complex navigation and resource sharing, enabling the colony to adapt dynamically to changing environments. Researchers have even discovered nuances in the waggle dance that communicate not only food quality but environmental hazards and hive preferences.

Drone bees, while often overlooked, play a critical genetic role. They leave the hive daily during the mating season to congregate at drone congregation areas (DCAs), where they await virgin queens. Mating occurs high in the air and only once per drone, after which he dies. Despite their short lives, drones provide vital genetic diversity.

The queen, typically the sole fertile female, can lay up to 2,000 eggs per day during peak season. Her pheromonal profile—especially the queen mandibular pheromone (QMP)—maintains social order, suppresses worker reproduction, and communicates her presence. If her pheromone output weakens, the colony begins raising a replacement, often through emergency queen rearing.

Bees’ daily behaviors are deeply rhythmic. Their circadian clocks regulate sleep, navigation, and foraging patterns. They can time their visits to flowers that release nectar at specific times, and some evidence suggests bees even anticipate events based on prior experience.

Foragers typically begin their fieldwork after about 21 days in-hive. These seasoned bees exhibit extraordinary homing skills, capable of navigating several miles using landmarks, the sun, and Earth’s magnetic field. Their ability to detect polarized light and memorize floral odors allows them to locate and communicate food sources efficiently.

The hive’s division of labor, rapid communication system, and mutual dependency are hallmarks of a true superorganism. Understanding these internal dynamics helps the treatment-free beekeeper appreciate how best to support—rather than disrupt—this naturally elegant system.

Evolution and Physiology

In observing bees in the wild—especially feral or unmanaged colonies—we can see how they adapt freely to their environments. Feral bees often nest in tree cavities, walls, or cliffs, and they exhibit strong hygienic behavior, diverse genetics, and self-sufficiency. These wild colonies typically follow a more natural rhythm: less brood in dearth periods, increased propolis use, and frequent swarming. Unlike managed hives, they aren’t interrupted by constant inspections or synthetic treatments, and their comb is built entirely to their specifications.

These feral examples offer a powerful model for treatment-free beekeeping. They show us what bees do when left to thrive on their own terms, highlighting behaviors and adaptations that commercial systems often suppress. Observing or rescuing feral swarms can also help reintroduce genetic diversity and resilience into domestic apiaries.

The evolutionary path of bees also explains many of their modern traits. For example, their pollen baskets (corbiculae), hairy bodies, and barbed stingers evolved as adaptations for both defense and pollination. The evolution of eusociality—where a single reproductive queen is supported by sterile workers—allowed for incredibly efficient colony-level adaptation, especially in fluctuating environments.

Equally important to their development is the co-evolution of bees and flowering plants. Over millions of years, angiosperms (flowering plants) and bees developed a mutualistic relationship: flowers evolved nectar and bright colors to attract bees, while bees evolved specialized structures and behaviors to access nectar and transfer pollen. This tight evolutionary dance has resulted in many species of plants that are entirely dependent on bees for pollination—and in turn, bees that rely on those plants for food.

The diversity of flower shapes, scents, and bloom times corresponds to the capabilities and life cycles of various bee species. Honey bees, in particular, exhibit floral constancy, meaning they tend to forage on one species of flower at a time—an adaptation that maximizes pollination efficiency. This trait has had a profound influence on the evolution of flowering plants, shaping their reproductive success and geographic distribution.

Bees also exhibit a range of temperature regulation adaptations. They shiver their flight muscles to generate heat in the winter and fan their wings for evaporative cooling in the summer. These mechanisms, combined with wax-capped honey reserves, allow bees to maintain remarkably stable brood temperatures even in variable climates.

Interestingly, their circulatory system does not pump blood but hemolymph, which bathes organs directly and transports nutrients and hormones.

Their sensory system is equally impressive—antennae detect minute chemical changes and their feet taste surfaces they walk on. Such sensory complexity enables them to detect floral resources, hive health, and even stress in fellow bees.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the honey bee’s success lies in its ability to collaborate, adapt, and specialize within a group dynamic. This resilience is what treatment-free beekeeping seeks to honor and amplify.

Caste Differentiation and Social Harmony

Bees also demonstrate exceptional thermal intelligence as part of their caste and community management.

Nurse bees regulate brood temperature by clustering, fanning, or moving brood cells. This thermoregulation directly influences caste development, especially in early larval stages. Warmer zones may promote faster development, while cooler zones signal delayed roles. This refined environmental control further illustrates how tightly interwoven biology, behavior, and environmental sensitivity are within the hive.

Such intelligence is not just instinctual—it reflects an evolved form of collective decision-making. Every bee contributes to a shared outcome, with tasks and physiology shaped by feedback from the entire colony. Recognizing this gives us deeper respect for the hive as a sentient, dynamic entity—not simply a machine of production, but a conscious community whose needs and rhythms are worthy of reverence.

In a healthy hive, there are three main castes: queen, drone, and worker. Each caste arises from the same basic egg, yet diverges dramatically based on nutrition and environmental cues during larval development. This process—particularly the exclusive feeding of royal jelly to queen larvae—triggers genetic expression patterns that shape physiology, behavior, and lifespan.

Recent research into epigenetics reveals that environmental conditions can play a crucial role in caste determination. For example, temperature during the larval stage can influence gene expression pathways that contribute to the development of queen versus worker traits. Nutrition is another decisive factor: while all larvae are initially fed royal jelly, only those destined to become queens receive it throughout their development. The composition and duration of this feeding are key, as royal jelly contains a unique mix of proteins and bioactive compounds that activate the queen developmental pathway.

Even subtle variations in hive conditions—such as microclimate, pheromonal concentrations, humidity levels, or stress—can alter the trajectory of development. This dynamic response illustrates the bees’ extraordinary epigenetic plasticity and underscores the importance of maintaining stable, nutrient-rich, and low-stress environments in treatment-free systems. It also shows how bee biology is not only genetically determined, but profoundly shaped by the living conditions around them.

The queen is the mother of the colony, capable of laying both fertilized and unfertilized eggs. Fertilized eggs become workers or potential queens, while unfertilized ones become drones. The queen’s pheromones act as powerful chemical signals that coordinate behavior, suppress worker ovary development, and maintain colony cohesion.

Drones are larger, male bees that exist for the sole purpose of mating with virgin queens. They do not forage, defend, or work within the hive. Though often expelled in autumn when resources wane, drones are vital to genetic diversity, as queens typically mate with multiple drones from various colonies.

Worker bees display remarkable behavioral plasticity. Their tasks change with age—a phenomenon known as age polyethism. Young workers begin by cleaning cells and nursing brood, then progress to comb building, food storage, guarding, and finally foraging. This progression can be accelerated or delayed based on colony needs. For instance, in times of crisis, foragers may revert to nursing roles.

These roles are not rigid; they reflect a colony-wide intelligence. Bees respond collectively to stressors, environmental changes, and even disease outbreaks with task redistribution, behavioral shifts, and cooperative care. This social plasticity underlies the colony’s adaptability and strength.

All this coordination occurs with no central authority. The hive relies on decentralized decision-making, guided by a network of sensory cues, pheromones, vibrational signals, and mutual feedback. Trophallaxis—mouth-to-mouth food and information exchange—also spreads chemical messages that keep the colony updated and unified.

Understanding caste dynamics and behavioral flexibility is key to working with bees rather than against them. Treatment-free beekeepers who honor these internal processes—by minimizing disturbance and allowing bees to self-regulate—foster stronger, more naturally resilient colonies.

As we move into the next chapter, we will explore how these insights translate into core principles for treatment-free beekeeping.

These foundational values—rooted in observation, partnership, and trust—help us align our practices with the bees’ own wisdom and set the stage for a regenerative approach to hive care.